The Park

The Priory and The cell of St. Amphibalus

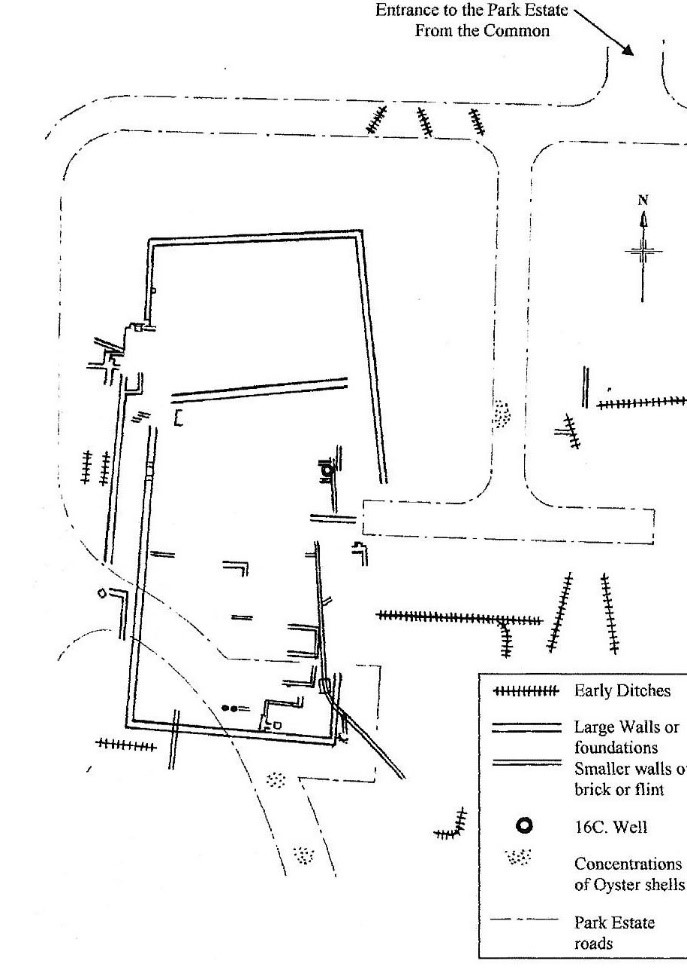

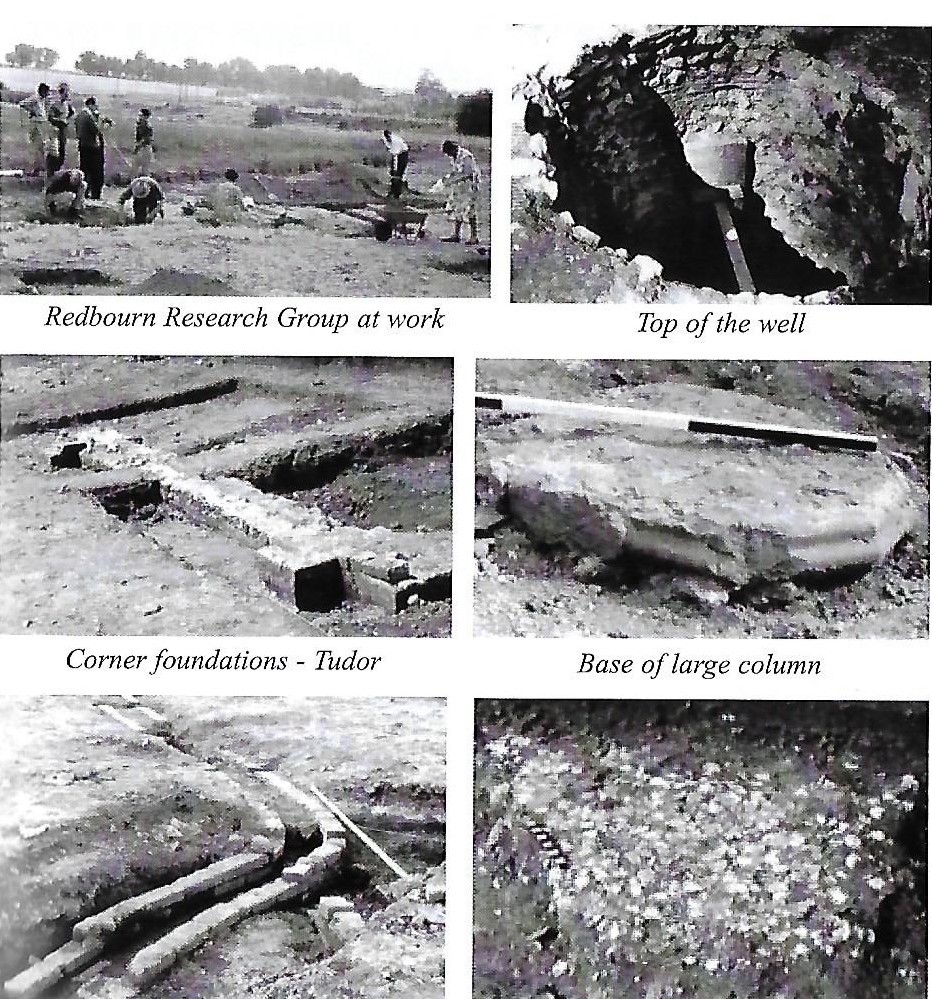

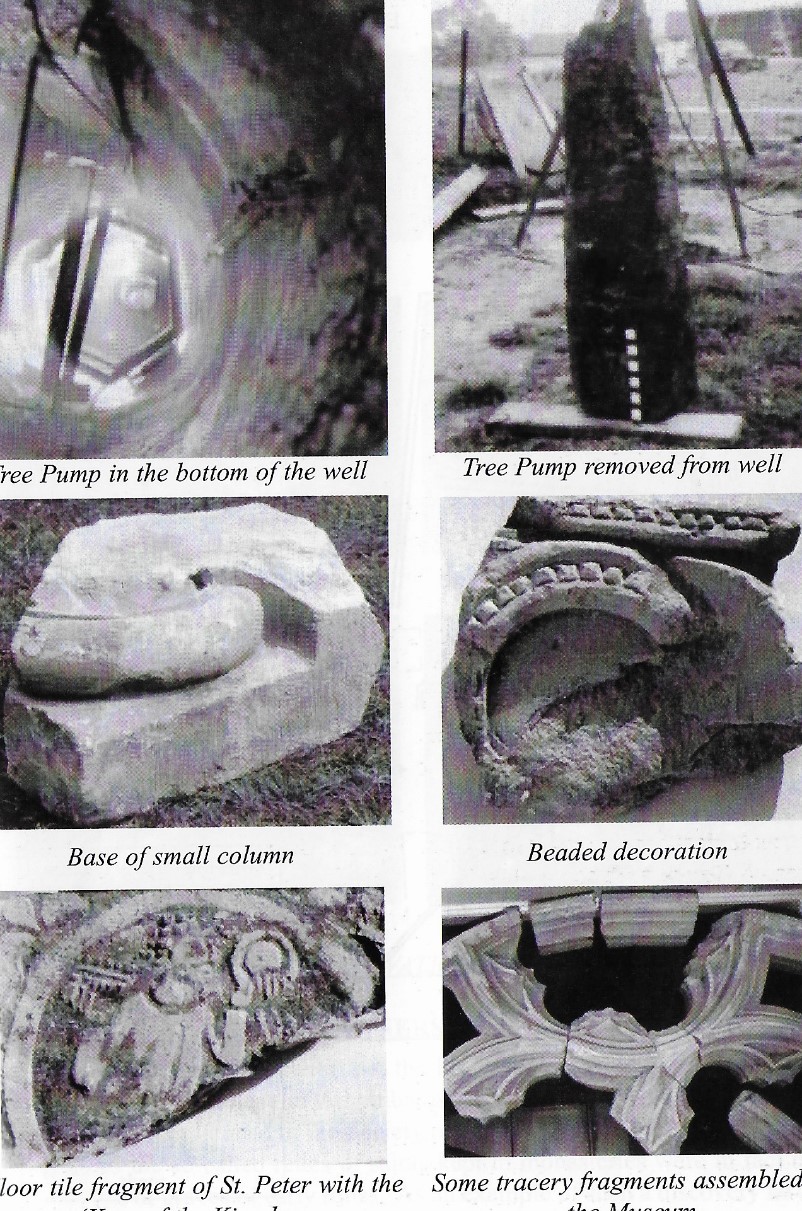

The ‘Park’ estate was built between 1966/7 and the Redbourn Archaeological group carried out some work on the area and a plan of the discoveries was made. Medieval ecclesiastical stonework from the 12th to 15th century was recovered and a well was dug out and at the bottom was a tree stump. This could have been the well referred to as ‘Amphibalus Well’.

Unfortunately, no large scale evaluation could take place but together the site and documentary evidence do point to the true location of the Priory. It has been suggested that the Chapel could have occupied the same area as Fish Street Farm House. There were many other building noted in the complex, so perhaps it was remnants of these that were found in The Park.

The cell of St. Amphibalus at Redbourn was established reportedly as the result of the miraculous discovery of the remains of St. Amphibalus (who had converted Alban to Christianity) and his fellow-martyrs in 1178. According to legend, St. Alban appeared at night to Robert, from St. Albans, and led him to the burial-place of Amphibalus and his companions in Redbourn. After marking the place for future identification, Robert returned with St. Alban, who disappeared when they arrived at his church. The story reached Abbot Simon, who sent some monks with Robert, and set a guard over the ground, the holiness of which was proved by miracles of healing. Exploration there led to the discovery of several bodies, one of which was identified by the manner of his death as that of St. Amphibalus. The remains were removed to the Abbey to join those of St Alban.

A more likely explanation is that the bones came from two burial mounds known locally as ‘The hills of the Banners’ and modern commentators have suggested that the remains from the mound were the subject of a managed spectacle by the church in St Albans being three days after the feast of St. Alban. The bones were conveyed to the Abbey with great pomp and the site of the burial was marked with the first chapel which would have been on the Norman style. Another later one more worthy of the saint was not completed and dedicated until 1215 as the chapel of St James and would have been built in the Early English style, with a single bell.

The cell was used by the time of Warin (1183-95) as a health resort a rest away from the harsh regime of the Abbey probably about once every three years. The priory and monks were attacked by the soldiers of Louis of France on 1st May 1217. According to legend a silver-gilt cross containing a piece of the Holy Cross, was stolen but soon recovered as the man who had stolen it started to fit violently after leaving the Priory, and became so violent that his comrades had to bind his hands and take him to Flamstead Church, which they meant to raid. At the entrance, he dropped the cross and it was picked up by the parish priest who inquired what it was. The robbers, thinking that they were being punished for the theft were terrified and begged the priest to take the cross back at once to the monks. It was possibly to compensate for losses then sustained that Abbot William de Trumpington (1214-35) gave to the house a beautiful psalter and ordinal and two gilded shrines. For the safety of the shrines and the relics in them he appointed a monk with a colleague to relieve him to guard them continually. During the time of this Abbot, the conventual church was consecrated by John Bishop of Ardfert.

By the time the Abbot Richard de Wallingford (1326-35) wrote the rules for Redbourn, the cell was more formally organised. The three monks taking their turn there were to remain a month, and were neither to go nor return on foot; a brother at Redbourn who by permission came to St. Albans, must be accompanied by his prior; the brothers were to go to Matins, say together the Canonical Hours, and hear the Mass of the day, and those who were priests must not omit for four days to celebrate mass; constant transgressors of these rules were to have their stay shortened; they were to take the air together in places removed from public concourse and return in good time for dinner; they were forbidden to visit neighbouring houses and friends or go beyond the boundaries without the prior’s leave, and to go on foot a mile beyond the priory, or stay the night anywhere without the abbot’s permission ;they must not eat before the common meal or sup in time of regular fast without leave of the prior, who was to be very careful how he gave it; their food was to be served daily from the kitchen of the abbey as for monks at St. Albans ;the prior and brothers were not to keep hunting dogs, hunt, look on at the sport, or leap over the hedges of their neighbours; they must not bring into the house persons of doubtful reputation to eat or talk with them, or have intercourse with such outside. Not much of a rest home!

There would also have been a dormitory, hall, cooking and washing areas. Later, there appears (about the 1340’s) to have been separate toilets for the monks and the Abbot (Thomas de la Mare). The rooms were well provisioned with couches, benches, tables, table clothes, tapestries being mentioned along with church ornaments such as vestments and chalices. The monks appear to have taken an interest in astronomy as part of an astrolabe was found during excavations on the Park Estate site.

There was no cemetery on the site and it could be that bodies were conveyed back to the Abbey on the River Ver as they arrived by St Germans Gate.

The arrangement about food did not work at all well: hot dishes sent from the Abbey were naturally not very palatable when they reached Redbourn, about 3 miles off. Abbot Thomas de la Mare (1349-96) solved the problem by allowing 5s. per week in lieu of food. He also simplified the matter of the priory’s supply of fuel. Abbot Thomas did much for the priory, giving vestments, plate, furniture and books, he also rebuilt the chapel of St. James, which had been burned down many years before, constructed a room in which to study with ‘windows on three sides’ above the Common lavatory which he could use both as a wardrobe and en-suite when he visited Redbourn. He was very fond of the place and frequently stayed there.

Thomas was also instrumental in making Thomas de Beauchamp Earl of Warwick in 1383, renounce his claim to Redbourn Heath. The dispute on the point had for years caused the Priory great inconvenience, for Flamstead men, relying on their lord’s support, had kept up a continual feud with the Priory. On one occasion they had seized the cart with the monks’ provisions and taken it to Flamstead and the Prior had been so frightened lest his food supply might be cut off permanently.

The stone walls round the outer court were repaired by Abbot John Wheathampstead (1420-40) There appear to have been two gates, one gave access to ‘the prior’s safe road’ which ran from the mill at Bettespool to Chequer Lane. The other gate looked onto the Heath and had been threatened by the men of Flamstead who wanted to pursue their ancient right to drive and graze livestock on the Health and use it as a route to the market in St Albans. Abbot John also gave £7 to improve the kitchen (probably built in the 14th century) and contributed £40 to decorate the chapel with murals and improve the altar. One William Stubbard built a cloister at the Priory between 1421 and 1440 in the Perpendicular style. However, by this time, the priory was falling into decline, sometimes there were only two monks there, and often the place was left empty. Wheathampstead ordered that with the Prior, they must number at least four, and they were to remain their appointed time without interruption unless recalled by their superior; they were to go to the chapel every day and say together the canonical service; at festivals Mass and Vespers were to be sung, and to help in the singing, two clerks were to be added to the house. It seems that on special occasions the people of the village used the church as well. St. Amphibalus was to be commemorated at Redbourn as at the Abbey; the brothers were each to celebrate mass daily, and that they might be the readier for their duty they were to go to bed earlier and abstain from late drinking, unnecessary meals, from roaming about and excessive recreation. They were to avoid doubtful places while on their way to the priory and were to bring nobody into the house from whom scandal might easily arise. The Abbot expected them to use their leisure time there in reading, learning, or other useful employment to prevent idleness. These rules were unpopular and not, it seems, obeyed or enforced.

When Henry VIII was declared Supreme Head of the Church in England in 1534, the list of all monastic property drawn up and valued the Priory at £9.2s.0d. When a price was drawn up for the sale of the Priory at the Dissolution of the Monasteries, it included a manor and a priory farm. In 1535, the Priory is mentioned as being abandoned.

The manor farm (Beaumonds) had meadows, pastures, rights of pasture, woodlands and coppices 53s 4d (£2.13s. 4d.) The Priory farm with 20 acres of pasture, land belonging and cultivated by the Priory, with cottages and tenements over £13. It was bought by John Cocks and his wife in 1540 when the chapel was mentioned as being still standing with some lead on the roof.

It is possible that this area is the location of ‘Place House’, built by Sir Richard Reade who came to the village in 1558. This house was possibly on the raised ground in the present day ‘Park’ estate where excavations found traces of buildings as detailed above. The house he built used stones from the Priory. Richard was born in Nether Wallop in Hampshire, second son of Richard Reade (died 1555) and Margaret. He was educated at Winchester College and New College Oxford, where he became a Fellow in 1528. He took a degree in Civil Law (1537) and became a doctor of Civil Law in 1540. He had a reputation as a man of ‘learning and experience’. He was made a Master of Chancery and went on a trade mission to Flanders for Henry VIII. He was knighted in 1544. In 1546 the Lord Chancellor of Ireland was charged with corruption and was dismissed from office. Read took his place, living in a house near St Patrick’s Cathedral. On his return to England in 1548, he became Master of Requests and he purchased the manor of Redbourn. He managed to continue his career amidst the uncertain political times of Edward VI and Mary I. He even took part in the heresy trials of Ridley, Cranmer and Latimer. He died on July 11th, 1576 and was buried in the Lady Chapel in St Mary’s. His wife is in the same vault. He left an extremely detailed will of over 200 lines, one of the finest to have survived from Elizabethan England. There were legacies to Winchester College and for the upkeep of the parish of Redbourn. The Manor of Redbourn was inherited by his eldest son, Innocent. It is not known when Place House went out of use and was dismantled.

The actual location of the Priory has been the subject of much debate. Study of documents suggest that the names of the fields of Fish Street Farm, Upper Park, Lower Park, The Park, Plough Park and two Park Fields would link this area to the enclosed land of the Priory. Calculations made appear to show that the total area is similar.